To me, Seattle collectively is a town of secrets, somewhat bereft of candor. The widely used phrase “Seattle Nice” connotes a passive-aggressive culture in which the locals say one thing sweet, then do something else not so sweet. Then there the “Seattle Freeze,” the notion that Seattleites are uncommunicative and unfriendly to newcomers. I am not alone in seeing evidence of both concepts.

To me, Seattle collectively is a town of secrets, somewhat bereft of candor. The widely used phrase “Seattle Nice” connotes a passive-aggressive culture in which the locals say one thing sweet, then do something else not so sweet. Then there the “Seattle Freeze,” the notion that Seattleites are uncommunicative and unfriendly to newcomers. I am not alone in seeing evidence of both concepts.

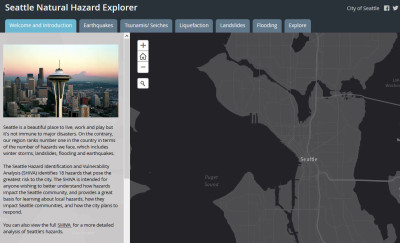

So it is refreshing to see the forthrightness expressed by the city government in an interactive Website that just went online. It’s called the Seattle Natural Hazard Explorer. The SNHE allows a user to zoom in and evaluate the propensity of a specific neighborhood or property for a host of natural perils. It’s even possible, as I did, to plot many hazards–among them, earthquakes, landslides, flooding, tsunamis and something especially scary called liquefaction–on the map and eyeball the entire city.

My takeaway: I live in one giant disaster-prone area waiting to happen.

Earthquake faults lace the city. Some 1,500 landslides already have hit Seattle in barely a century. Flooding is a big issue. Liquefaction–in which filled-in land turns into a fluid after an earthquake–could wipe out the entire neighborhood of Interbay.

Seattle pulls no punches. “Our region ranks number one in the country in terms of the number of hazards we face, which includes winter storms, landslides, flooding and earthquakes,” the SNHE homepage declares. Two years ago, the city produced a 297-report called Seattle Hazard Identification and Vulnerability Analysis. I have no idea if the report’s acronym, published on the cover–SHIVA–was a deliberate word play on the Jewish custom of mourning the dead for seven days by sitting shiva. But for good measure, the report’s cover includes a photo of a 1997 mudslide that took out a row of fancy homes along Perkins Lane at the bottom of the Puget Sound bluff in the Magnolia neighborhood, where I live.

If that’s not bad enough, there’s one other peril not specifically plottable on the map: the aftermath of an eruption of Mount Rainier. The snow-capped active volcano dominates Seattle’s skyline on those rare clear days–even though it sits 54 miles to the south-southeast–and is routinely called the most dangerous volcano in the country. There also Glacier Peak, 70 miles northeast of Seattle, officially classified by the feds as a “high-threat volcano.”

The same geology and geography that gives Seattle its breathtaking scenic beauty is also responsible for its peril. It took some mighty awesome forces of nature to create around Seattle the high mountains fronted by bodies of water so deep that floating bridges were needed because bridge supports would have to have been almost as tall as the 605-foot-high Space Needle. Those destructive forces of nature haven’t stopped.

The Nisqually Earthquake of 2001, which registered 6.8 on the Richter scale, was centered 50 miles southwest of Seattle but did a lot of local damage. An article last year in The New Yorker about when–not if–the Big One will hit Seattle drew regional notice.

Before becoming New To Seattle in 2011, I spent a fair amount of time looking at hard copies of maps plotting landslides to figure out how far back from the end of a bluff was safe for living. The SNHE would have saved me a lot of effort.

As I see it now, the SNHE with its power to inform is a blow against the Seattle Freeze. But Mother Nature remains the ultimate example of Seattle Nice.